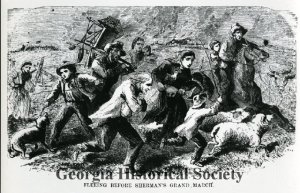

Fleeing before Sherman’s Grand March, date unknown. From the Georgia Historical Society Collection of Photographs, 1870-1960, 1361PH-21-20-5869.

The purpose of reanalyzing the American Civil War at 150 was to challenge preconceived notions of the reasons behind the conflict, the people who lived through it, and the consequences of a war that threatened to undermine the American experiment and undo the handiwork of the Founders. Utilizing new approaches to the study of this time period enables present day scholars to discover multiple layers of complexity that have rarely been discussed in the context of the war.

Many of the issues that divided the Civil War generation – race in American society, the growth and scope of federal authority, states rights vs. centralized power, the role of minorities in American life – are still critical to civic life in our own day. At the sesquicentennial commemoration of the Civil War, a greater understanding of these issues will be more important than ever. With a greater understanding of these new approaches to the war, it is hoped that instructors and scholars will be able to enhance the level of instruction about this critical period in American history in college classrooms around the country and thereby engage students to think critically about contemporary problems and conflicts.

The American Civil War was arguably the single most significant event in American history. If the Revolution established the United States and the Constitution its republican form of government, the Civil War preserved both from their greatest challenge. The Civil War created our modern nation. It ensured the survival of the United States of America, our republican form of government, and proved to the world once and for all the ability of the “People” to govern themselves. The Civil War prevented perpetual strife and anarchy by crushing the doctrine of secession and making America “one nation, indivisible;” abolished slavery and laid the foundation for a biracial society; affirmed our nation’s commitment to majority rule and acceptance of the results of legitimate elections as first established in 1800; and created the world’s beacon of liberty and the haven for millions seeking refuge, asylum, and opportunity over the past 150 years.

While all of this may seem self-evident, in the popular mind nothing could be farther from the truth. In the 1890s, as America became an Imperial power on the world stage, both Northerners and Southerners united to create the “Reconciliationist” version of the war: both sides fought valiantly for what they thought was right, leaders on both sides were honorable men, and race and slavery had little or nothing to do with the cause. By the 1890s (and ever since) both sides could lament the Reconstruction era as a tragedy, a misguided attempt to create a biracial society, which they claimed had never been a goal of the war. As Civil War scholar Gary Gallagher has recently noted, “The Reconciliationist Cause most often was characterized by a measure of northern capitulation to the white South and the Lost Cause tradition.” Lost in the process was the fact that, as Frederick Douglass noted in 1871, loyal Americans should never forget that a Confederate victory would have meant “death to the Republic.”

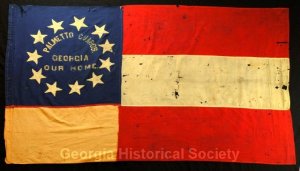

Company colors of the Palmetto Guards, Company C 19th Georgia Infantry, 1861-1865. From the Georgia Historical Society, A-2398-001.

As Jim Crow became the law of the land, white Southerners and Northerners shook hands across the bloody chasm and agreed to lay aside the more fundamental issues of what caused the war in order to achieve reconciliation and racial solidarity as America entered the world stage at the turn of the century. In this view, there were no traitors to the United States; states rights, not slavery, was the root cause of the “conflict;” and the conflict itself became a “War between the States” rather than a Civil War between the forces of the national government and an insurgent uprising bent on destroying the United States in order to perpetuate the institution of slavery. With few exceptions, this Reconciliationist interpretation prevailed until the nation entered the Centennial remembrance of the War in the early 1960s (which also coincided with the Civil Rights movement), and outside of academic circles, continues in force in popular culture to the present day. It was forged at the expense of all those – black and white, southern and northern – who fought to defend the government of the United States against the most formidable and dangerous internal threat it has ever faced.

The Civil War was a conflict of unprecedented scale and bloodshed that resolved two issues left unresolved by the Founders: 1) Is the United States a creation of the states or of the people – a loose confederation of states that could at any time reclaim their sovereignty or an individual nation established on the principals of representative government and majority rule? And 2) would the United States continue to sanction human slavery, an economic and social institution inherited from the colonial period but increasingly incompatible with the nation’s stated commitment to the cause of liberty? With these questions in mind, you can delve into the stories of place and scholarly lectures within this site spanning the causes of the war, the choosing of sides, slavery and emancipation, and the war as it is remembered in our collective history and memory. This journey will challenge you to stand on different ground, closer to the actual historical evidence, stripped of all the layers of romanticism that have prevailed since 1865, and help you understand the conflict from the point of view of those who participated in it from 1861 to 1865.

The American Civil War has historically been celebrated through re-enactments and public programming that does more to glorify the war rather than emphasize Lincoln’s “rebirth of freedom.” The Civil War was a tragedy that sacrificed over 620,000 American lives and left hundreds of thousands more scarred or maimed for life. Yes, there was heroism on both sides, but that heroism needs to be set in the context of the causes of the war as well as the unprecedented violence and suffering that engulfed our nation from 1861 to 1877, inclusive of the Reconstruction period. Heroism must not be separated from the cause that produced it. Remove yourself from your comfort zone, cast aside preconceived notions you may hold surrounding the war and its participants, and explore new scholarship and ideas that presented new perspectives on the era in order to gain a deeper and more honest understanding of the conflict.